We’ve talked about Rock Paper Scissors before. But let’s explore some extensions of the classic game.

Rock Paper Scissors

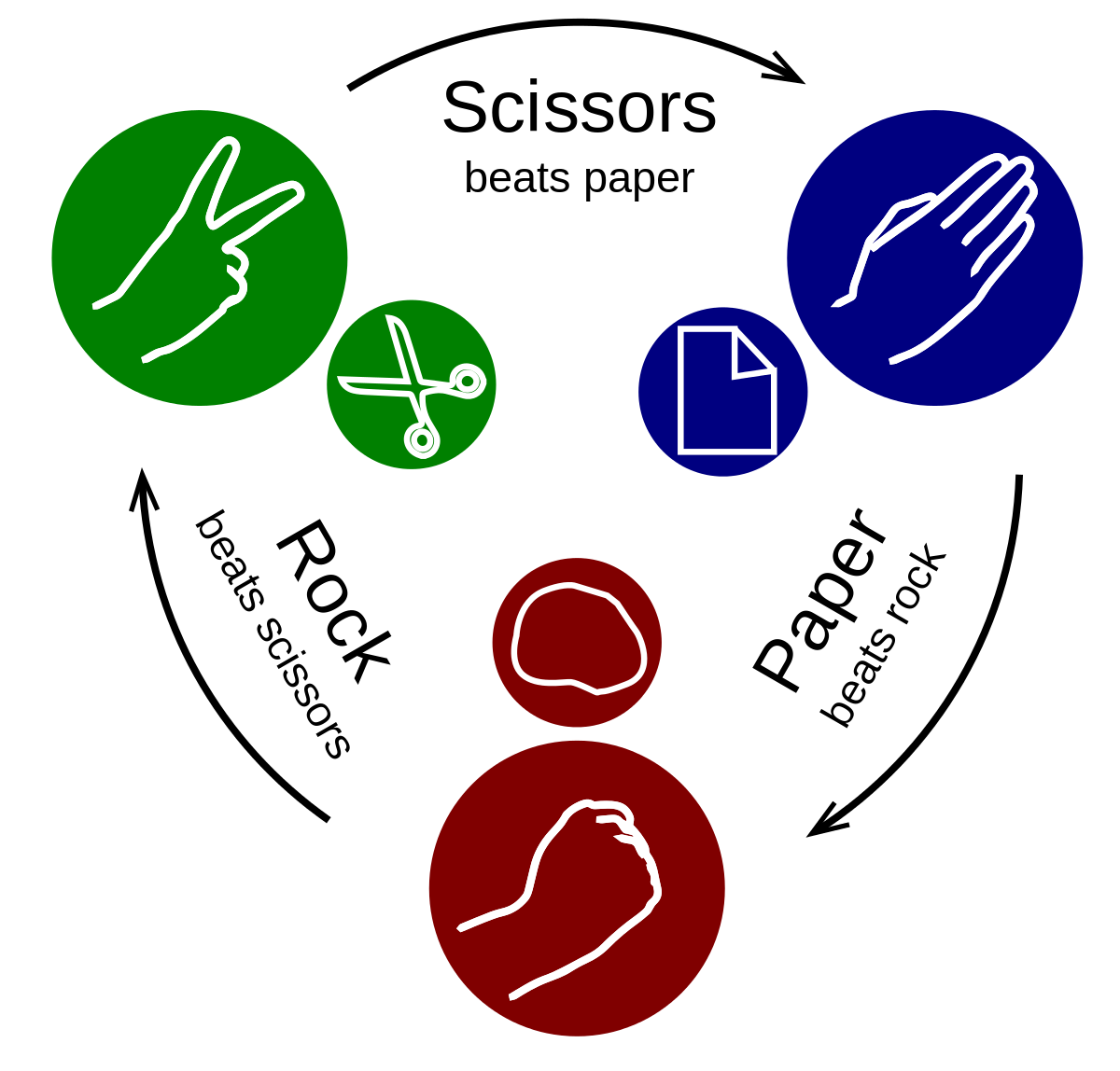

The normal game of Rock Paper Scissors involves players simultaneously choosing and revealing a move. The three choices are “Rock”, “Paper”, and “Scissors”, with victors determined as in the image above. I’ll call such an image a ‘victory graph’, where arrows point from the move that wins to the move that loses.

Rock Paper Scissors, as a game, is ‘random’ because there is no one move that is objectively better than the others—all moves win against one other move, lose against one other move, and tie against themselves.

Rock Paper Scissors+

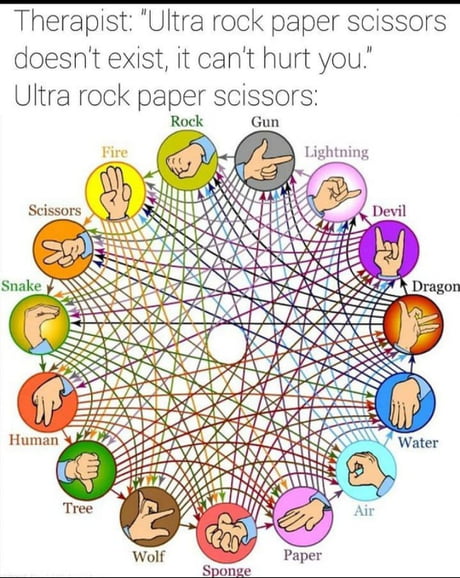

Now, lets try adding another move to the game, for example “Lizard”. Can we edit the victory graph shown above to make the game ‘random’ again? In other words, can we have each move win against the same number of other moves and lose to the same number of other moves? Try it out!

Turns out, it is impossible to make a ‘random’ Rock Paper Scissors Lizard game. For example, if we kept the victory graph the same for Rock, Paper, and Scissors, making Lizard beat Paper and lose to Scissors/Rock, the game would not be ‘random’ anymore. Choosing Scissors or Rock would be better than choosing either Lizard or Paper, since Scissors/Rock win against two moves each while Lizard/Paper only win against one each.

Recalling the previous blog post, this doesn’t mean that Rock Paper Scissors Lizard has a Nash Equilibrium: there is still no equilibrium because there is no one move that beats all the others. But the game is still less random than we’d like.

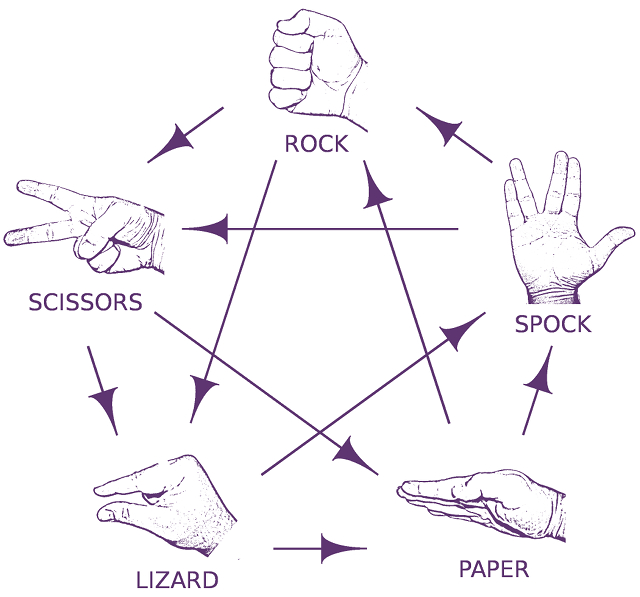

This logically leads us to ask: then, for which numbers of moves can we make the game ‘random’? For example, five moves works, leading to the “Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock” game, as Sheldon explains.

And here is the corresponding victory graph:

Now on to the math…

Okay then. Let’s try to characterize which numbers of moves work. Consider having n moves arranged in our victory graph as vertices. In the victory graph, every edge connecting two vertices is drawn in, and each edge has a direction, pointing from the winner to the loser. Furthermore, in a ‘random’ victory graph, each vertex must have the same number of outward edges, and the same number of inward edges.

We’ve seen that n=3, n=5 work, while n=4 does not. If we think about it logically, it seems that only odd numbers work. Can we show this rigorously?

First, let’s show that each vertex must have an equal number of ingoing and outgoing edges. To do this, suppose that each vertex has the same, non-equal numbers of ingoing and outgoing edges. But since each edge is counted once as an outward edge and once as an inward edge, these counts must be the same, which fails in this case. Hence, each vertex must have an equal number of ingoing and outgoing edges.

Next, consider when n is even. It’s quite clear that this won’t work, since we need an equal number of ingoing and outgoing edges, meaning that each vertex has an even number of edges attached to it, which isn’t true when n is even (since each vertex has n-1 edges attached to it).

Finally, we move on to the case where n is odd. It seems that this will work, since we can have an equal number of ingoing and outgoing edges for each vertex. But we don’t really know that this will work for sure—at least until we prove it.

We can use math induction to prove the desired result: the “falling dominoes” type of proof where we show that small cases imply larger cases, then prove the simple small cases to solve the entire problem in one fell swoop.

Okay, so for the small case we can show that when n=3, we can make a valid rock-paper-scissors game. This is true, because its simply normal rock paper scissors.

Now we suppose that there does exist a valid rock-paper-scissors game for n moves. Can we show that it is possible to add two more moves to make another valid game? Indeed, let’s call these two moves A and B, and we can assume that A beats B. Then we can make A win against exactly (n-1)/2 of the remaining n moves, while B wins against the other (n+1)/2. The game is still random, because each move still wins against an equal number of other moves. So there we have it! We can be sure that completely random rock-paper-scissors games exist for all odd n!

Afterword

Thanks for reading :P this article was pretty long, but I hope you found the exposition somewhat clear/intuitive. I thought of this interesting problem as I was taking my APCS test and couldn’t resist writing it down in a post!